A glance back and forwards at the 2021 version of ‘Rugby’s Greatest Championship’, as the Six Nations likes to call itself.

Bill Sweeney, the RFU’s CEO, has given his views on its future. He is strangely half-hearted about it. ‘We need to be a little bit more innovative in our thinking…’ Why ‘a little bit’? Those who have the women’s championship at heart have been crying out for decisive change for ages. The 6N committee has shown itself unadventurous over recent seasons. Only its sensible reshaping of the Covid-ridden 2021 campaign showed it at its best.

Format

The committee deserves great credit for coming up with that new format to mitigate worries over risk-taking, and the spread of contagion. The loss of two games from the usual five meant each round having a greater significance, a heightening of tension.

The one inequality of the three games per nation concerned the final round, where the teams in Pool A, England, Italy and Scotland, had the undeserved benefit of home advantage. As fate would have it, Italy surrendered it to the Irish who would have been quarantined on their return. Lo and behold, all three home teams won on Super Saturday. And if the draw had been reversed?

The pity was, a set of finals on neutral territory was precisely what could not happen. A final between Ireland and Wales in Rome has its attractions.

Should the new structure survive?

The current pattern is simple: everyone plays everyone else once a year, but with six nations involved that brings an imbalance of home and away games.

As I have argued before, that number 6 is not set in stone. Add other nations to the brew and the programme would extend much further. Clubs would feel the loss of leading players and the players themselves would find absence from work or study a bigger problem.

The system of pools introduced this year could be extended, so that total number of tests would be safeguarded through pool-rounds and play-offs. Players were excited at the prospect of competing in a rare final, and the pairing-off of teams in the same position in the two pools meant close matches and more excitement.

You don’t need to be a revolutionary to argue for more nations joining in the fun. That is one sure way of promoting women’s rugby across Europe. Promotion/relegation is a thorny topic, but one that must be broached.

Timing

Observers have been calling for a switch from the traditional February-March slot for a long while. It took the arrival of Covid-19 to make it a reality and it turned out to be a great success. The better weather was predictable; the chance for players to have more time to prepare for international-standard rugby during lockdown was less obvious but just as welcome.

This meant making a decisive break from the men’s version of the 6N, another move which many had felt to be urgently needed. As it turned out, the coverage afforded the women’s tournament did indeed expand enormously. More on that later.

Keeping the April slot will mean an adjustment to the season of all six unions. In England for example the Allianz Premier 15s league will either be completed before the 6N starts or the knock-outs left till May.

In that way the 6N would become the natural climax to each season. One concern is be whether players might not be more exhausted after a full club programme than hitherto.

Adding to the complexities is the new world calendar which may well be introduced in the next season or two.

Media

Media coverage expanded exponentially. For the first time all games were available on free-to-air television. Feelings were mixed as viewers saw the efforts of the BBC to cover the first round. These were restricted to their iPlayer platform, rather than one of their national stations. Coverage was patchy. In the hands of experts the commentaries were fine, but the befores and afters were gravely lacking; even the half-time interlude fell far short of expectations. Auntie responded by adding her red button to the offerings of later stages – a step in the right direction.

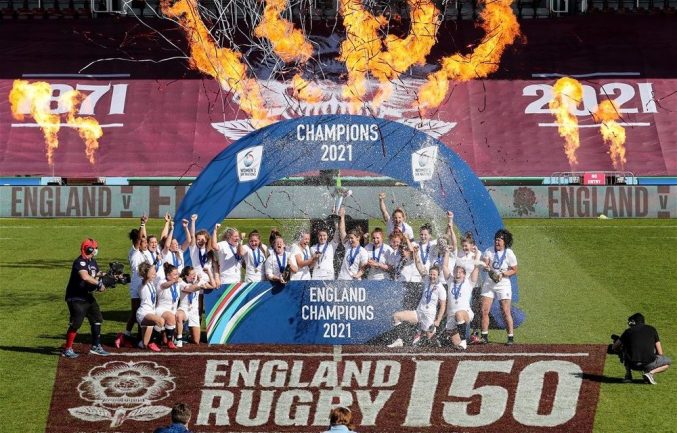

The crux of the matter came with the final round, which would involve England at home. The assumption all along was that the opposition would be France and that they would be tussling for the top spot – and so it turned out. No prizes for that. Would the BBC throw its full weight behind the event? The answer was a resounding Yes.

The sports department called up all its biggest beasts to front the show: Gabby Logan at pitchside as the anchor; alongside her Maggie Alphonsi and Nolli Waterman, two of the most recognisable figures in English women’s rugby, and Ugo Monye, who has made such an impression in recent times with his considered views on the game.

Up in the crow’s nest were the lead commentator, Sara Orchard, backed by Mo Hunt. Orchard may count herself the best female commentator in the country. Listen to her covering a hockey match; a far greater challenge than rugby for any commentator. And Mo Hunt added her ultra-sharp analysis without giving way to self-pity for her enforced absence from the pitch. Her knowledge of her team-mates and staff added greatly to the viewers’ understanding of the game, especially those new to it.

One maddening feature BBC2 retained was the artificial crowd noise that never seems to chime with what is happening on the pitch. On the ground itself the tension was palpable; not even the bursts of song over the loudspeakers during gaps in play were necessary to keep everyone hanging on the moment.

And now we have the viewing figures: a high of 600,000, which Sweeney terms disappointing. And perhaps it is, but it compares favourably with other figures. Scrumqueens reports: ‘As some form of yardstick, the Premiership’s semi-finals of 2020 had a reported peak of 205,000 viewers’. One crucial concern is to keep the championship on free-to-air television.

As for the game itself: it fell short of being the all-dancing, all-singing extravaganza we may have hoped for, but it lost nothing it grit, pace and excitement.

Before and after each round all forms of the media, especially the social platforms, helped to make the public more aware of what was happening. Background pieces on individual players served to humanise the business and create new personalities. The main target was the young. If this had been an election campaign, you suspect the candidate would have won a comfortable majority.

PS What were the viewing figures for the umpteenth showing of Flog It! ?

Standards of Play

It was strange to find Sweeney describing the two teams in the final as ‘rusty’. ‘Error-prone’ is surely nearer the mark. The French had all been playing since September – with interruptions due to positive tests – the English since October. This was in stark contrast to the other four nations, few of whom enjoyed any club competition before the 6N. They were the ones who had to overcome rustiness, and they achieved it mightily.

The Red Roses and les Bleues are quite used to playing each other; the one difference at the Stoop was the introduction of the word ‘Final’, which can affect the mind and body by its rarity.

For the rest, the continuing advance of women’s rugby was there to be seen. Just imagine what the standards might have been if the pandemic had not happened and every player had enjoyed a full season’s activity.

Ongoing Problems unsolved

These problems are well enough known: the lack of sponsors, the professional-amateur split, the unevenness of the competition. None of them has seen a marked improvement this year. The pandemic has affected people’s lives and events to a shattering extent. How might the Six Nations have moved on in normal circumstances?

For the 2020-1 season the Premier 15s announced the Allianz insurance company as its new main sponsor. The Six Nations remains without one – despite frequent expressions of optimism.

While all countries have been starved of the game at grass-roots level, the variations at elite level have been plain to see. Within the 6N only three countries saw any club rugby during the 2020-1 season, and even they varied enormously. Italy managed to stage a single round of matches; France’s Elite 1 was dogged by repeated postponements; only the English Allianz Premier 15s has fought through to the latter stages with postponed matches all being replayed successfully. For the Irish, Scots and Welsh nothing.

The ongoing unevenness of the 6N was exaggerated by these inequalities. At its extreme: the England squad met up regularly for training at various comfortable locations; the Welsh enjoyed minimal time together. Once Warren Abrahams arrived on the scene things improved, but the slowness of the WRU’s search for a new head coach is reflected in Wales’ second year with the wooden spoon.

Only in the final round of Super Saturday did margins of victory reduce to heart-stirring levels: 4, 7 and 20. Here like played like; the winners of the two pools against each other, and so on.

The volume of criticism of certain unions has grown ever louder. For anyone used to the idea of a clear pathway from beginner to test cap the lack of an Under 18 or Under 20 squad seems improbable. But that is how things stand in more than one competing nation. The WRU and the IRFU have come in for a real pasting at the hands of critics, often ex-internationals who have seen old structures allowed to decay or promises to develop new ones come to nothing.

At least the noise is now so deafening that action is likely. The ever present worry is lack of funding.